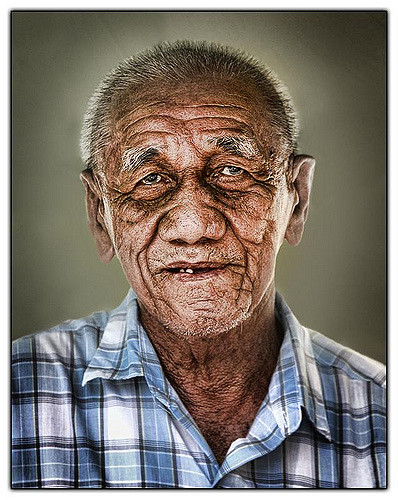

A view of Georgetown from the top of Penang Hill

Photo Credit: Sarah Watts

It was 11pm on a Saturday night when we finally arrived at our hostel on Love Lane in Georgetown Penang. We had hit the party street. There were drunken tourists but also a lot of drunken locals and to be honest, I didn’t feel overly safe. We snuck into the 7/11 on the corner for something to eat and bottle of water before hustling back to our room for a much needed sleep.

When we woke up late Sunday morning it was a completely different city. The streets were filled with locals and their trishaws, food carts and knick knack stalls. The sun was hot but the humidity was something I had never experienced. You could tell the locals by the way they handled heat.

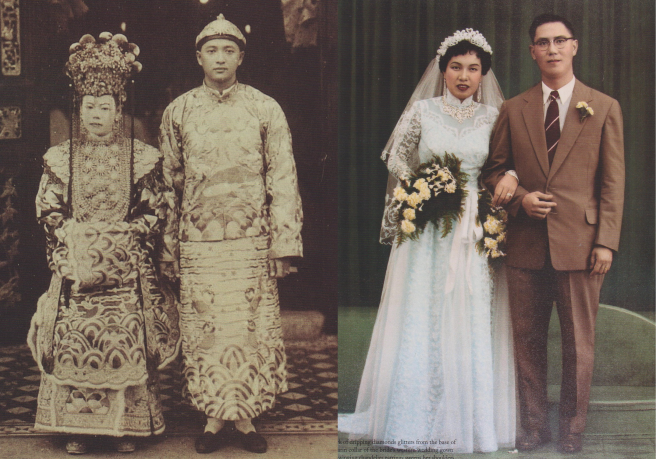

It soon became obvious that we had arrived in the midst of Chinese New Year and the extent of the celebrations surprised me. It seemed as if the whole city had become immersed in the traditions and this was just the beginning of my realisation that Georgetown, Penang was the most harmonic, multicultural functioning city I had ever experienced.

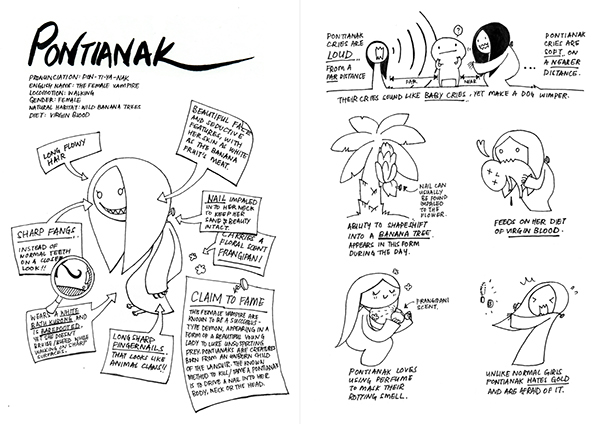

The three main races of Georgetown are the Malays, Chinese and Indian but there is also a multitude of religions practised including; Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, Sikhism, Taoism, Confucianism. This combination of ethnic group resulted in the formation of the present day Penang Malays who developed their own socio-cultural practices, language and religion. It was because of this extensive mix of cultures that I found it so interesting that the celebration of the Chinese New Year was so prominent. What other religious or traditional festivities were practised and were they to the same extent as this one?

Walking through the streets alone these religions and cultures began to jump out at you, not just from the everyday happenings of the people but because of the amount of traditional temples and places of worship. Prayer and worshipping were (and remain) integral part of the lives of Penang’s original settlers, these places also developing into meeting points, uniting those who professed a similar faith.

During our 14 day stay in Georgetown is definitely became clear that certain areas of the city were occupied by certain cultures and lifestyle customs. This however, did not detract from the fact that the city remained to be peaceful and smooth functioning in terms of accepting and adopting one another’s cultures and customs.

References

Inc., G.T.W.H. 2014, George Town World Heritage Site, George Town World Heritage Incorporated, Accessed April 23, 2016, <http://www.gtwhi.com.my/index.php/introduction/george-town-world-heritage-site>.

Nasution, K.S. 2012, ‘George Town, Penang: Managing a Multicultural World Heritage Site’, Catching the Wind: Penang in Rising Asia, Accessed April 23, 2016, pp. 20-41.

‘Penang State Museum’ 2016, Personal Interaction, Georgetown Penang, Malaysia, Visited February 16, 2016.